What follows is our story. It describes the Musée de la civilisation’s efforts to provide our fellow citizens with relevant content during the first months of lockdown. It also tells of how this digital transformation had a long-lasting effect on our professional practices and garnered widespread media attention. Let us begin.

Those first days of lockdown seem like ages ago now. At first wondering “How am I going to reschedule?,” I soon came to think “We’re going to have to revamp everything!” During a conference call on that first Monday of lockdown, the team felt strongly that the Musée had to be there for our community. But what does that mean when the Musée is closed and all of us are at home in lockdown ourselves? Since the arts and culture can bring well-being and purpose, especially in a situation rife with boredom and anxiety, we readily agreed that “being there” meant we should repertory online content for people to browse. That way, they could virtually spend an hour “at the museum” anytime they wished, even though we were closed.

It seemed like a good idea, but we were already facing many issues. Most of our online content rounded out our physical exhibitions and therefore lacked context on its own. Our website was outdated, and nothing near user-friendly. Like I said, we were talking about a total overhaul here.

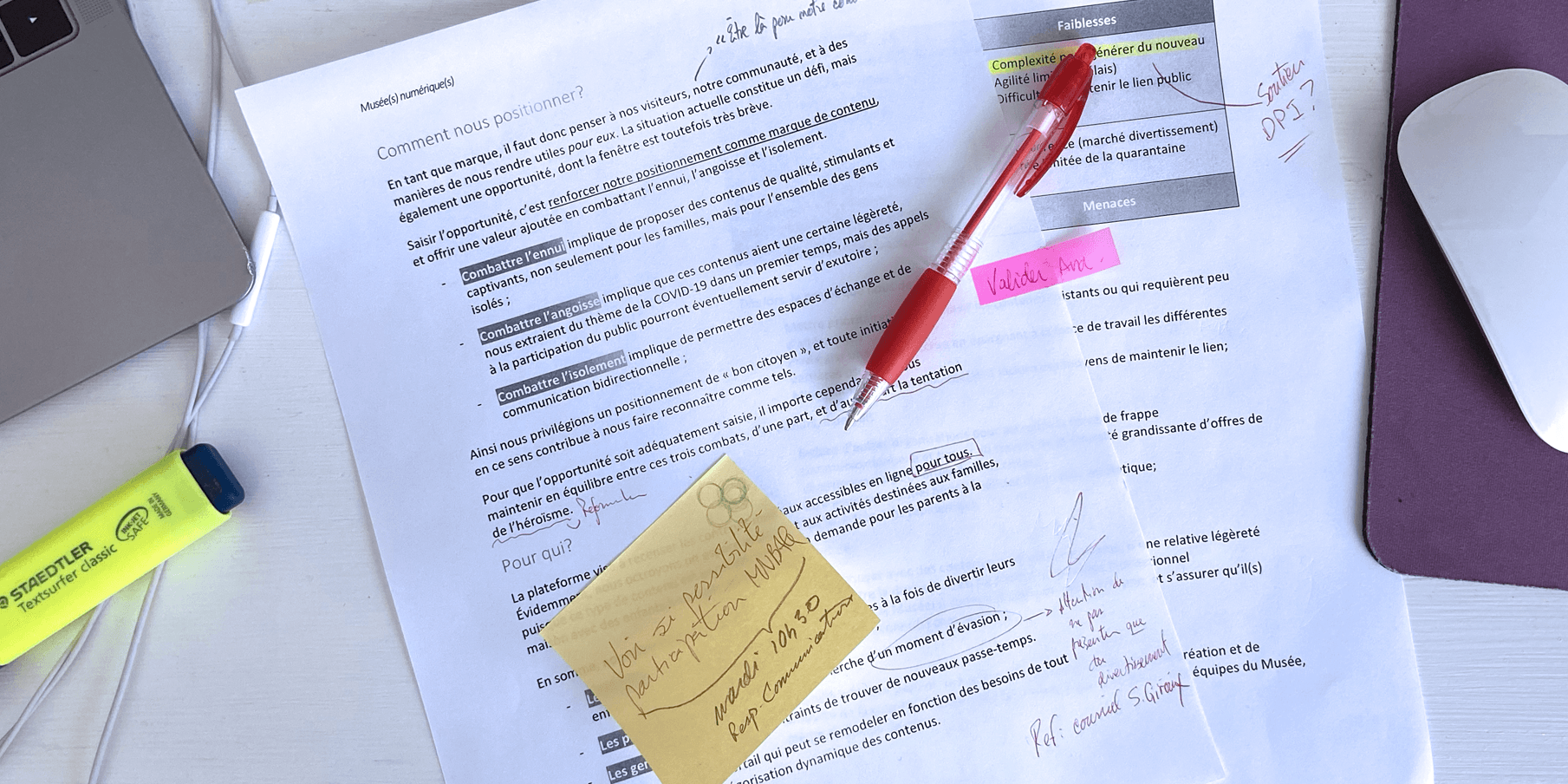

I began sketching out a project, without even knowing if I would get a dollar to make it happen! I thought, “Well, let’s put up a simple WordPress. We can share our content, some new texts. We’ll put it all in context and give it a new spin to make it family-friendly and turn it into a really nice browsing experience.” A kind of a blog, with new entries every day or so.

Meanwhile, some colleagues decided it was high time for our exhibitions to be available in virtual reality (VR). So they sent a guy—just one—to take 3D pictures of every single room in the Musée, the totally empty Musée (on a Saturday too!)

Three days later, we had our new website! And 3D visits of our exhibitions were in the works. Okay, so the website was ugly and confusing. And, I mean, let’s face it wasn’t unique: we were just one of a few thousand museums with online content. What’s the point? How is that relevant? And why would people browse our list instead of stuff published in the newspaper or wherever?

The Musée de la civilisation might not be the biggest museum around, but still is a state-run institution created by the Government of Québec. If we were going to ask people to come “to the museum,” shouldn’t it be any museum? We needed to invite other museums to join us!

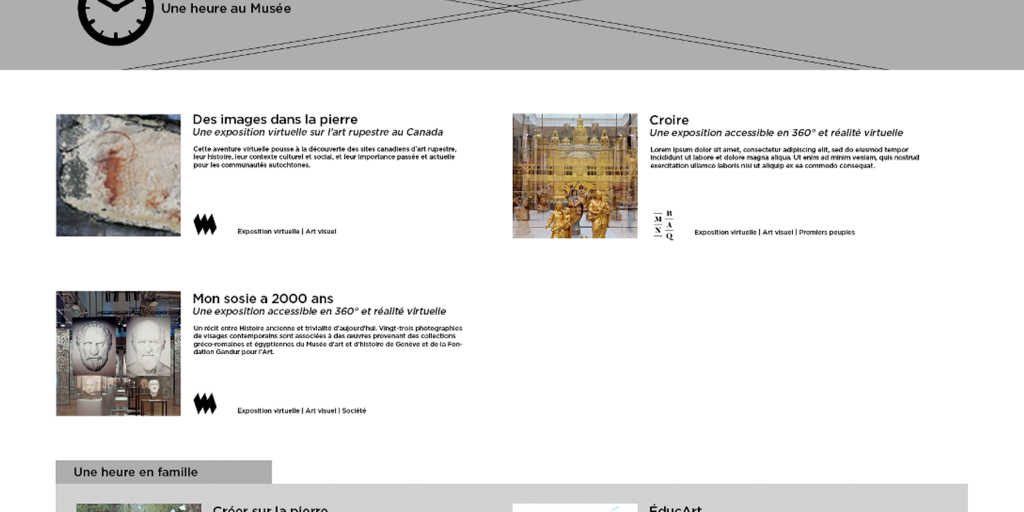

So, we scrambled together some money and rang a web agency, saying “Here’s our little project, help us make it big!” And they did, with designers and programmers literally working day and night. In less than a week, we had “Une heure au Musée,” our virtual museum-visit platform providing French-language articles, podcasts, pre-recorded lectures, demonstrations and discussion panels, games and virtual exhibitions to visitors around the world.

We were ready to open up our project to other museums and cultural organizations with a view to helping our partners share their content and to fulfilling our promise of publishing new content every day. The platform grouped everyone’s content as one website, which then redirected visitors to each individual partner’s pages. This facilitated searches, thanks to appropriate SEO, and grouped content by thematic or age-group cross-searching segmentations. This would not have been possible if the publications had been limited to social media, or the content only available on partners’ respective websites. It was easy for both humans and search engines to find our cultural content!

What did this teach us? First, that it’s worth the effort to act quickly, even though we didn’t have the time to think our ideas through fully. And second, that alone we could go only so far, but together we could work in everyone’s best interest. All the partners did indeed immediately benefit from the social media announcement, thanks to our pooled fan bases, email contacts and member bases. Since our partners were spread across Québec, our project got plenty of media coverage, even as early as March 25!

Seeking relevance and engagement

A question was still irking us, however: Is this what “being there” for our community means? For instance, is it what a teacher would do with a student going through tough times? Wouldn’t a good teacher try to help and make sense of what was happening? They wouldn’t entertain and distract; at the very least, they would acknowledge their protégé’s experience. Isn’t that what we should be doing, too?

What’s more, the pandemic was a unique moment in human history. As one insightful colleague reminded us, the Musée de la civilisation is a society museum and, as such, needed to document citizen experience and the pandemic’s material culture. We needed to find out how our fellow citizens were experiencing this, how they felt about it and what will go down in our collective memory. We had to start identifying what artifacts the Musée needed to collect. History was being written now, and we had better pay attention and keep track of it for posterity.

Back to the drawing board. (Like I said, a redesign). We quickly developed another section of the website, called “Documentez la pandémie!,” in which we invited citizens to share their stories. They could choose to answer a question or submit photos or drawings, or whatever we thought we should ask for. In a few days, we received dozens of testimonials. It was obvious that people had a need to express themselves and share what they were going through!

Ah-ha! This was what a museum should do in a pandemic!

Or, wait, was it? Just when we thought we were getting somewhere, doubts resurfaced. Our two initiatives were presenting people with a lot of entertaining and educational material and they could share their stories if they wanted. We were strengthening partnerships with other museums, getting lots of visibility, increasing reach, and documenting how citizens were experiencing the pandemic.

Yet, we weren’t exactly developing a deep connection with our visitors. First of all, there were no incentives or reminders to come back after their initial visit, even though the website was getting bigger and more interesting with every passing day. And second, it was based on a traditional top-down communications model, with just one way to provide feedback. We were still far from a conversational engagement model!

That’s when we shifted perspective, from caring teacher to friend. If we truly wanted “to be there” for the members of our community, we had to reach out. We had to write and talk to them directly, with the right tone, about their experiences and what’s important to them.

We had to keep in mind that the Musée was still an organization with economic imperatives, aiming for reach and growth or, at least, to maintain what we had. In other words, we still had our own agenda. And furthermore, our mission is not only to entertain; it is also to educate about the various aspects of society and to conserve and present artifacts. For these reasons, we added two new sections to our website: the Rendez-vous, and an email subscription.

The first addition consisted of straightforward 30-45-minute live broadcasts on Facebook that we visibly announced on the website’s header as not-to-be-missed events. Lightheartedly (except during a few technical difficulties!), I interviewed my fellow colleagues: the masterminds behind our exhibitions or the curators speaking about an instructive yet fascinating subject, like depictions of Rome, which offered up a little vicarious travel. As a pretext for discussing best collection practices, we even talked with one of our archivists about his private collection of PEZ dispensers! We also offered this spotlight to our partners, some of whom took us up on the opportunity.

The second addition was an email subscription form allowing visitors to sign up to be notified about new content published on the platform. While we could have just added these new subscribers to our usual, CRM-based mailing list, we decided to keep them apart because we wanted these emails to be different, friendlier and more caring, and to feature content from everyone involved in our two initiatives. To share this new list with our partners on-demand and to strike a totally different tone from our usual emails, we set up a different mailing system. Every other morning or so, I’d get up early and email those soon-to-be one thousand contacts. I’d let them know about some fresh content on our site and mention the news we’d all heard the day before, trying to gauge the vibe of society and respond accordingly.

I signed those emails personally and they were sent from my own professional address. This began as a mistake, but we soon realized that the personal touch actually served us well. As a matter of fact, I started receiving replies every now and then, most of them simply thanking us “for still being there in these tough times.” That’s when I caught on that we’d reached our initial goal: being there for our fellow citizens and offering them content they felt was relevant!

From then on out, we had a fully working “system” with everything from a static top-down content offering to live entertainment and educational experiences. And it had a few feedback opportunities, like incentives that got people telling their own stories, a real person on the other end of an email and the possibility of joining in a live chat during the broadcasts. The more we added to the platform, the more the media were interested in our project. The more they heard about it, the more other museums joined us—11 in all, from all around Québec.

What more did this teach us? That big organizations (or even a group of organizations) can indeed have and demonstrate real authenticity. Putting a face on it—a person with their own humour, weaknesses and interests—certainly helped, though there was a thin line between “authentically representing the organization” and “showing off”! I’d love to say I have some insight to share on this one, but I have to admit I didn’t always succeed. We’ll have to give it more thought!

A hard monster to feed

So, by now it was April and here we were with these two new initiatives. For the most part, we were satisfied with both the engagement we’d achieved and the notoriety we and our partners were getting from all the functionalities and content. Yet, this project had put a lot of pressure on the whole Musée team.

It was a lot of work to fulfill our promise of fresh content every day, walk our partners through adapting their content to our platform, and compensate for the numerous shortcomings of our own content, especially so it could be published without the physical exhibitions it was most often designed to support. It was huge, when we didn’t even know if the Musée would be reopening or when, and if we also had to stay on track with our normal projects.

Furthermore, our team in the digital engagement department is small, and we didn’t just need help, we were in the dark. We didn’t know what content we should develop or if we could share existing content that had been developed but not yet published. In April, we finally set up an informal committee of experts from all of the Musée’s departments to design and propose various opportunities and evaluate content we had on hand. Since I was coordinating this committee, I kept hearing suggestions like “You could publish this magnificent artifact from the reserve” or “Why don’t you do a Rendez-vous with a curator about this or that piece in our exhibitions?” But, as I pointed out, a magnificent object is not content. Until we have something to say about it that could interest our public it is nothing but an artifact! So tell us, why does the item matter? Do we have pictures of it? Who will write the story? Could anyone draft the talking points for the Rendez-vous? At this point, I have to admit my immediate teammates and I truly felt overwhelmed and were seriously tired.

Nevertheless, our progress was visible. As the platform was cumulating more and more content, the urgency to feed it every single day diminished. It helped that everyone was starting to realize what exactly was expected of them. Seeing examples of basic ideas that had been turned into digital content, team members could better develop their suggestions before bringing them to the committee. By May—so about two months after the launch of “Une heure au Musée”—a lot of our colleagues had gained a deeper understanding of what digital content is. They were now suggesting truly relevant ideas, fit for the web and many different audiences. They were also more aware of the relentless pace of this “hungry monster,” and some even visibly enjoyed the challenge of keeping a step ahead of it!

We can now say that this was the Musée’s first quantifiable digital transformation that occurred during the project. A sure sign is that many teams decided to go even further and developed a digital-only programming for the 2020 fall season! As for the platform itself, some of our colleagues had a clear idea of how to ensure its longevity, deepen the relationship with our audiences and strengthen their own digital skills! Clearly, we’d have to keep up!

The “miracle” of user-generated content

As we better understood what citizens needed and wanted us to offer them, we also realized just how keen they were to share their stories. Every week over the spring of 2020, we received anywhere between 30 and 300 answers to our “Documentez la pandémie!” question.

Meanwhile, the Musée teams had clarified their intentions and oriented content development to turn the platform into a place for real conversation with our community. We asked a different question every week that was closely related to current events or to specific aspects of lockdown: “What do you miss the most?,” “What do you think about lifting the lockdown?,” “How do you imagine your summer vacation?” As the replies inspired more questions, we really felt like we were chatting with community members.

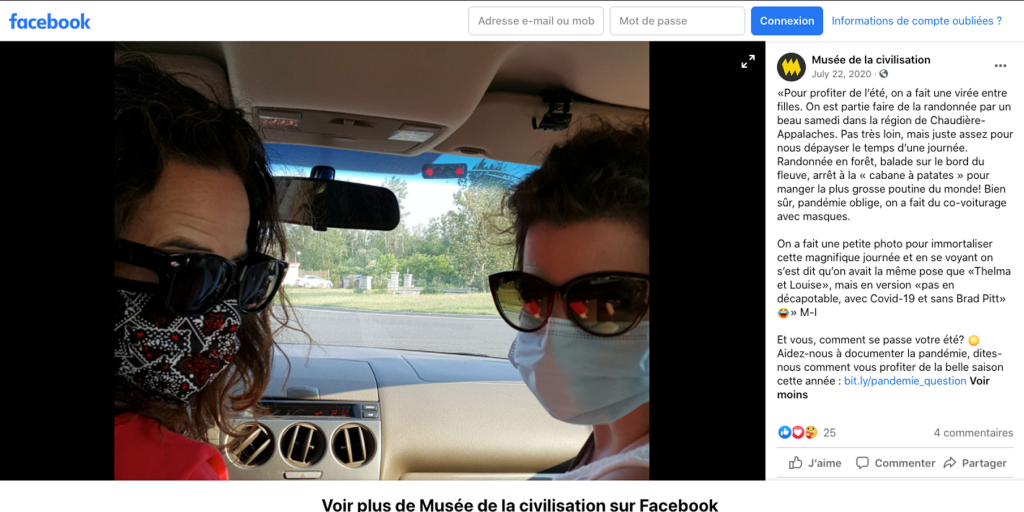

But as summer set in, participation rates fell. We slowed the pace and started publishing some answers on our social media to keep the conversation going. We also targeted specific audiences. We hoped to stir participation among people of different ages and from all across the province or, for some questions, of specific groups like essential workers.

This social conversation encouraged other citizens to document their experiences and soon the project took on a life of its own. We were no longer producing most of the website’s new content. Citizens were. Plus, we were refining our understanding of the moment and we understood without a doubt that everybody was fed up with the pandemic!

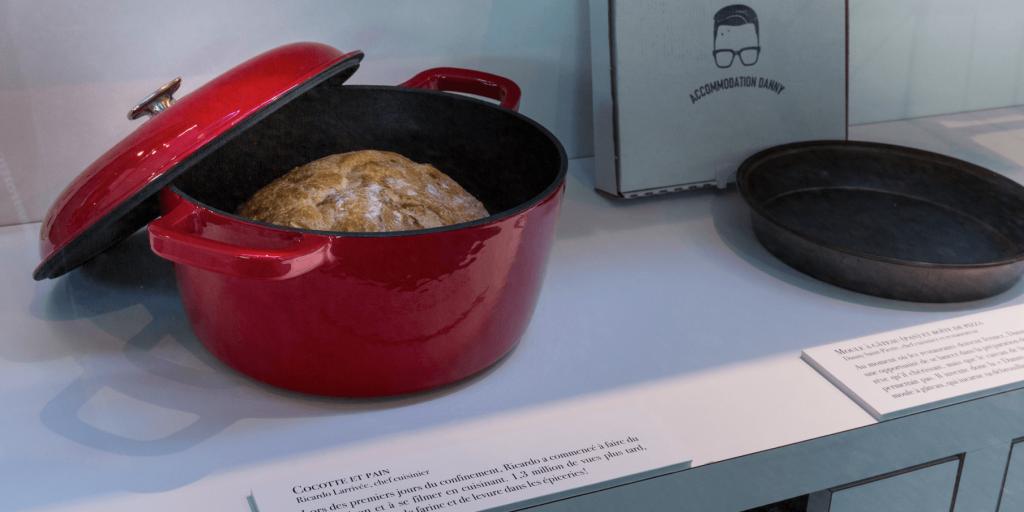

At the same time, we felt an urgent need over the summer to collect objects, before all the rainbows that had decorated our spring were headed to the trashcan! Just before fall, we launched the call for objects. To encourage donations of drawings and other objects, we called on artists, restorers, journalists, and other public figures. We asked for their artifacts of the pandemic and, with surprising speed for the Musée, we made six video clips. While we were at it, we decided to exhibit these objects.

The Musée had reopened a few months before and attendance was encouraging. In less than a week, the exhibition project manager and her team presented about 15 objects in a display case in the Musée’s hall. Never had our teams organized an exhibition in less time, but we knew our subject intimately, for having worked on it for months! The display case showcased objects as varied as a National Assembly press card, a bottle of disinfectant from a local distillery that had reinvented itself for the cause, the buttons from the emblematic FEQ summer festival, the 2020 edition of which wasn’t held, and a bread pan and homemade loaf made by Ricardo, a famous chef who had gotten Quebeckers baking during lockdown. In addition, two touching artworks made by women commemorated the tragic underbelly of the pandemic.

And we invited journalists to come see it. It was a hit on both traditional and social media. The images of the display and the video clips got thousands of views, and the Musée has received nearly a hundred proposals of other objects. Because, yes, we are still a museum interested in artifacts!

We’d finally come full circle.

But let’s remember how it all started. We felt we had “to be there” for our community and, while we used a whole lot of stuff and we talked a whole lot, in the end, we mostly listened. We asked. We questioned. We tried to understand. And everything fell into place almost on its own as soon as we followed what felt natural. From a place of empathy. User-generated content had truly worked for the Musée for once, and we could concentrate on what we do best: trying to explain it all.

What can be explained, and what is poetry

It might seem obvious that we just did what had to be done. We might have come up with all of these ideas upfront by simply taking a look at the situation and sizing it up. But the thing is, for most of us, this is our first pandemic. It is also the first and—let a guy hope a little—the only lockdown we’ll ever have to go through.

In other words, although with hindsight we can easily explain our process, what actually happened was a transformative story for everyone who took part in it. A story of resilience and successive hands-on learning about ourselves, as museum workers and citizens, and about our society.

Even though Québec’s Premier kept repeating “ça va bien aller”—it’s going to be all right—on his televised daily live press conferences, citizens’ concern was palpable in their testimonials. People were accepting, adapting to and coping with the evermore-restrictive public health recommendations, but since they had been deprived of human contact, they were also fully appreciating the strength of social ties. Yet, at the same time, this imposed break was doing them good. The step back it afforded was allowing them to better comprehend the frantic pace of daily life. They savoured family time and taking things more slowly. The thousands of testimonials we received also expressed empathy for those fighting the virus and for the bereaved.

I remember colleagues relating how they’d cried as they read these testimonials. The stories we received transformed our understanding of the pandemic, its consequences and effects on the elderly and on youth. It also shifted the course of our actions, since we quickly realized that the stories were of public interest and therefore needed to be shared right away. This can still be explained by opportunism or insight; we are not yet in the realm of poetry.

As we read the stories, however, we also felt we were supporting people in their misery. Some days, we even felt we were no longer just museum workers; we’d become, a commiserate character woven into the storyline—now, that was poetry!

I increasingly understood what our COVID exhibition team meant when asking for objects that tell a story and that have taken on new meaning during the pandemic. They in turn also came to better understand the tone and content that made for the engaging stories our digital engagement team wanted to share on the website and on social media, tools the curators had up until now preferred to avoid. They even began to appreciate the strength of the digital tools we were putting in place. These were helping the curators do their jobs at a time when visits to donors or scouting the province for new artifacts was not possible. Some even started to feel that working online was advantageous, as it was an opportunity to develop the same connections with a greater number and variety of donors. We started to be more intuitively aware of each other’s roles. That, too is poetry.

Many museums around the world felt the same urgency to take action when the lockdowns began, resulting in a great variety of initiatives. However, to our knowledge, few have worked on as many fronts as we: offering content, initiating and pursuing conversations, collecting both testimonials and objects, putting certain artifacts on display and, inspired by our fellow citizens’ responses and our every action, learning what our role as museum workers should be in such tough times.

Now, that might not be poetry, but it is synergy. And part of this coming together was digital transformation, of course.

And we can now say that the very last of a whole series of lessons we’ve learned since March 2020 is that the Musée de la civilisation’s purpose was not “to be there for our community.”

Rather, it was “to be there with our community.”

???????? Musées et pandémie: qu’avons-nous appris? ????????

2020 a mis en lumière l’inventivité et la résilience de nos musées.???????? En marge de #Museumnext, joignez-vous à nous sur l’application Clubhouse pour discuter l’expérience québécoise et francophone! ⚜️

Quand: jeudi 25 février, 15 h 30 (HNE)